A Famous Graph of the Triumph of Science Actually Shows Just What is Wrong with Our Agriculture

It’s the most reproduced chart in anything ever written on agriculture. It shows a triumph of science: the meteoric rise in US corn yields following the adoption of hybrid corn.

Brief explanation: “hybrid” is used loosely to refer to any mixture of differences, but it has special meaning for corn (and some other crops). Corn plants produce pollen that floats on the wind to pollinate other corn plants; they almost never pollinate themselves and when they do, their offspring tend to be sickly from “inbreeding depression.” This was the last thing corn breeders wanted.

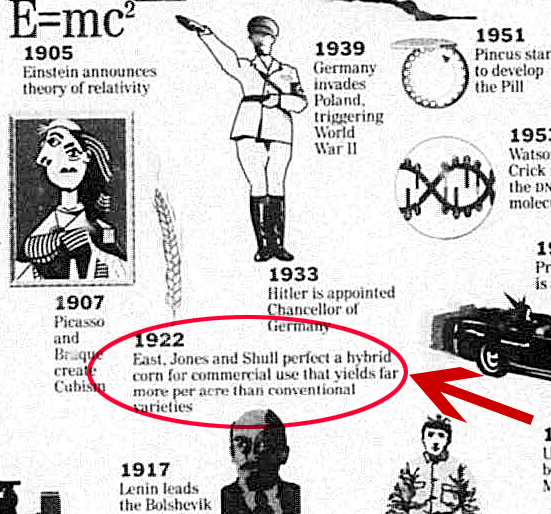

At least until around 1900, when scientists rediscoved Mendel, whose research on heredity — now known to every high schooler — somehow flew under the radar his 1860s contemporaries. By the 1910s “Mendelian” crop breeders in the US were adopting the new strategy of inbreeding corn, creating separate fields of sickly but pure-bred strains. Then when they crossed these inbreds, sometimes the offspring had “hybrid vigor” and higher yield.

A few commercial hybrid corn brands appeared in the 1920s, then more in the 1930s and 40s. Farmers were skeptical at first, but during the 1940s, hybrids spread; as one agriculturalist put it, their “dramatic improvement in yield potential must have truly seemed like a miracle.” Corn yields, which had barely budged in the previous 50 years, shot from 19 to 43 bushels between 1934 and 1948.

This breakthrough has been praised in almost religious terms ever since. “Little did Malthus know,” said a US government publication, that “hybrid corn would delay for almost two centuries the impact of his dire predictions” that food production could never keep up with population. Hybrid corn has even been hailed as one of the greatest achievements of the millennium, compared in importance to nuclear power, and credited with checking the spread of Communism [1].

Little wonder that that chart has been reproduced many times over [2].

But another reason for chart’s popularity is that it’s actually about much more than corn and hybrid vigor. It reflects and reinforces the important belief that agricultural science is there to keep us from starving — or eating each other like in Soylent Green. As Norman Borlaug, the “father of the Green Revolution”, put it in his 1970 Nobel prize acceptance speech, “we are dealing with two opposing forces, the scientific power of food production and the biologic power of human reproduction”. The claim that hybrid corn saved lives helps to validate the subsequent waves of technology.

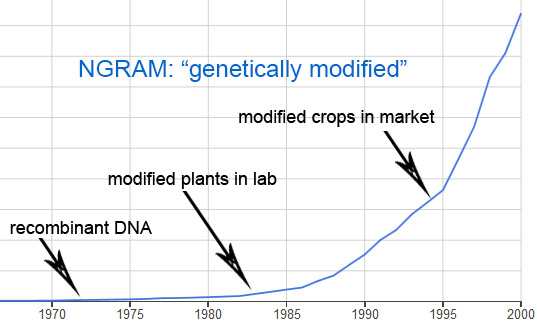

Here, for instance, is professional biotechnology booster CS Prakash posting his version of the corn graph to endorse genetically modified crop technologies.

And it is true that corn yields have been tending upwards ever since the late 1930s. But everything else that has been inferred from the chart is wrong. The chart is actually a textbook of everything that is wrong with American agriculture.

All crops were rising

First, attributing rising corn yields to hybrids is sleight of hand. If someone told you they had a teenage growth spurt because they ate their Wheaties, you would probably point to the counterfactual, to use the technical term: the non-Wheatie-eating teenagers grew just as much! By the same token, when they tell you corn yields took off because of hybrid technology, shouldn’t you ask if non-hybrid crops took off just as much?

Turns out non-hybrid crops took off more.

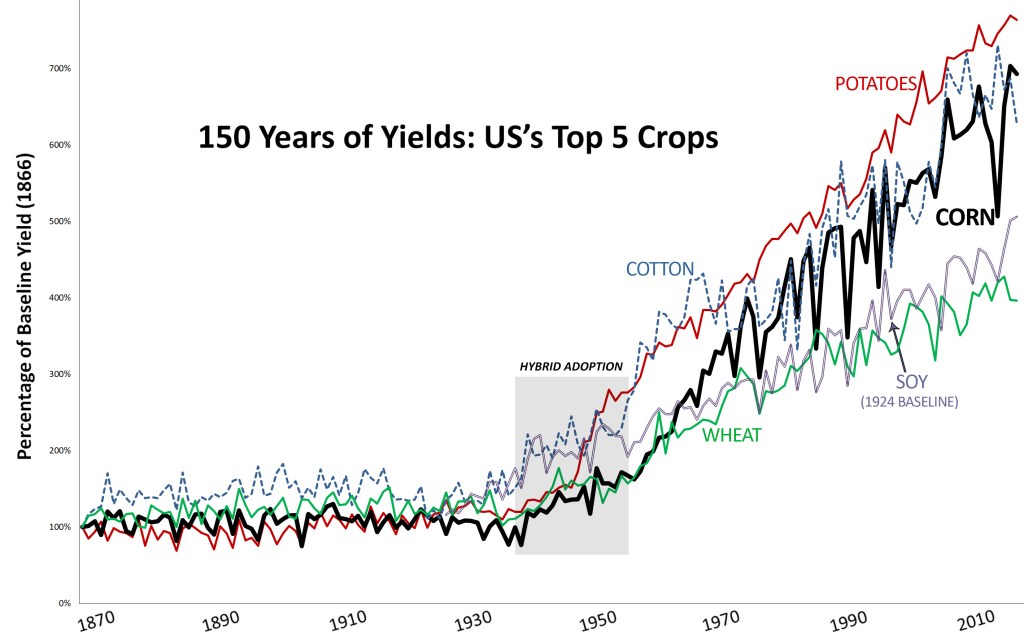

This figure shows the history of yields for the US’s top 5 crops. The pattern in unmistakable: all of these crops took off in the 1940s, and none were hybrids except corn. In fact, corn yields were growing more slowly than most non-hybrid crops.

The reasons for the upturns are no secret. While hybrid corn was spreading, fertilizer use more than doubled, pesticide spread, and mechanization rose — including a fourfold increase in mechanical harvesters and tractors between 1935 and 1955. [3, 4] In terms of productivity, hybrid corn was no breakthrough at all.

But what a breakthrough for seed corporations, for whom “hybrid vigor” would allow them to get their snouts deeper into the government trough than they ever had before.

Hybrid Vigor and Corporate Welfare

The concept of hybrid vigor is widely misunderstood. Saying that offspring of crosses of pure line varieties exhibit hybrid vigor is like saying that playing roulette makes you rich; the vast majority of offspring from inbred crosses show no hybrid vigor and are not even productive at all. This was known from the beginning of Mendelian breeding; in fact Erich von Tschermak – one of the scientists who “rediscovered” Mendel – stressed as early as 1901 that breeders would have to plant huge numbers of hybrids to find the rare offspring with superior performance. “Given only 100 inbred lines,” asks Jack Kloppenburg, “there are 11,765,675 possible double-cross combinations…[h]ow could all those crosses be made?” [1].

Moreover to be of economic value, the offspring had to not only outperform farmers’ corn, but beat it enough to warrant the expense of buying seeds. That’s because “hybrid vigor” only lasted for one season, and if seeds from the hybrid crop were saved for replanting, yields would plummet.

In other words, it was hardly an agricultural breakthrough; hybrid corn was an uneconomic, needle-in-a-haystack strategy that would require a vast amount of land, time, and work by breeders.

But it was a breakthrough for the Mendelian breeders in public institutions (like the USDA, land-grant universities, and agricultural experiment stations), because it allowed them to publish more scientific research articles and raise their status in the competitive world of science. In 1913 the American Breeders Association refashioned itself as the American Genetic Association and replaced its American Breeder’s Magazine with the more scientific Journal of Heredity as its official publication; its other publication, the Proceedings, doubled the amount published during the teens.

But hybrid breeding was an even bigger breakthrough for seed companies, which managed to convince the public breeding sector to do most of the hundreds of thousands of test plots and then turn over the haystack needles to the companies to sell for profit. Congress sent a gusher of money to help finance the work; the 1925 Purnell Act allocated up to $60,000/year (= about $1.1 million today) to each state agricultural experiment station, mainly to breed hybrids.

Of course it is not surprising that tax payers’ money would support basic scientific research that eventually leads to commercial products; that’s how things should work most of the time. But by the 1940s, the hybrid corn takeover led to the shriveling and then disappearance of the conventional “selectionist” breeding that had been developing and providing free improved seeds to farmers across the country. That corn yields had not been rising was not seen as a problem; in fact throughout the 1920s as Mendelian breeders were taking over the public breeding sector, the country was suffering from overproduction.

Overproduction: Gas on the Fire

The enormous irony of the famous chart of scientific triumph is that the surge in yields was the last thing the country needed. Agricultural — especially grain — overproduction had been a gathering problem through the late 1920s, and prices were crashing. Congressman Miles Allgood said that the overproduction problem was bad enough that research was needed to develop crop diseases!

And the proposal was not entirely tongue-in-cheek; as the former Alabama Commissioner of Agriculture, he had seen suppression of the boll weevil cause overproduction to the point of disastrous oversupply and realized that the boll weevil had been the “best friend the cotton farmer ever had”. The citizens of Enterprise AL famously erected a statue honoring the boll weevil, although people kept stealing it so they put up a resin replica.

Many farmers were irate about what government-supported science was bringing to their door. Even Henry A. Wallace, founder of Pioneer Hybrid Seed Company, admitted that “the farmer has a quarrel with science; for science increases his productivity, and this tends to increase the burden of the surplus” [5].

One of the first things Franklin Roosevelt did after taking office in 1933 was to push through the Agricultural Adjustment, an bold and unprecedented intervention that tackled overproduction in two ways. First, it bought up large amounts of surplus, paying well above the market price through price support programs that have been with us ever since. Second, it shelled out over $100 million in precious Depression-era dollars for farmers to plow under 10 million acres of cotton and shoot 6 million piglets [6].

This helped some but the corn surplus was intractable, and in some places grain elevators were charging farmers three cents per bushel to take corn off their hands. Corn production dipped some, but was back up to an all-time high by 1942.

Since then, the surpluses have only gotten worse. During the 1950s the government was buying up more excess grain than ever, and trying to get some Cold War mileage out of it by shipping it to countries where the Soviets had a foothold. Still the surplus grew, accelerated by the spread of the insecticide DDT — which epidemiologists later found to have predisposed millions of girls to breast cancer later in life.

By 1960 the government was spending the equivalent today of $5.4 billion/year on grain storage [7]. The overproduction crisis was the biggest domestic issue in that year’s presidential race between Nixon and Kennedy, with both candidates claiming they could manage the problem (Figure <1960>).

But the problem was about to get much worse.

Post-WW2 America was awash in cheap fertilizer — mainly due to the “beating of swords into plowshares” by converting munitions factories to fertilizer production. Breeders found they could raise yields even further (!) by adapting corn hybrids to ever-more densely crowded fields, and plants would soon be planted twice as densely as in 1955 [4]. The packed plants could be heavily fertilized, but they also had to be pesticide-sprayed and well watered. A nation suffering from too much corn grown with too much pesticide now got even more corn grown with even more pesticide.

Forced onto the Dole

The forces that pushed the corn yields through the roof in the 20th Century forced a profound change in the economics of running a farm. Seed, which used to be produced on the farm, now had to be bought. Corn now required chemical fertilizer every year (which also undermined the natural fertility of soil, locking farmers into a fertilizer treadmill [8]). Pesticides also became a major expense, likewise addictive as insects and weeds developed resistance. Tractors were so expensive they required a mortgage, with relentless payments that eroded the financial flexibility farmers needed [9]. When GM crops came along, they too required an extra ante. While crop production, already excessive by the 1930s, began its inexorable climb in the 1940s, production costs climbed even more steeply. The “march of progress” made the industrial American farm increasingly impossible to operate without substantial government support, and programs for proliferated rapidly.

Which leads us to an interesting addition to the famous graph. The USDA provides the numbers on the different kinds of dole American farmers have relied on since 1933. If you download the data and put it into a chart (with some programs lumped for legibility) you get this:

Out of morbid curiosity I put the payments into a cumulative graph to see how much the farmer dependency has cost us taxpayers 2.1 trillion. And a graph of the accumulated payments looks an awful lot like the famous climb of hybrid yields.

Even with this much dole, American farmers have still disappeared — gone under, gave up, or in many cases committed suicide. [12]

The famous chart’s rising line indexes a decades-long debacle for farmers, the government, the public, and the environment. The only winners have been the ever-expanding world of agricultural input industries.

How Did Farmers Get Into this Jam?

Predictions are hard, Yogi Berra once observed, “especially about the future.” If you could have told American farmers in the 1930s that the new hybrid seeds would play a key role in a century-long worsening of the agricultural surplus problem and the vanishing of most farmers, with the remaining ones heavily dependent on government aid, and that it had all been subsidized by taxpayer dollars, they would have been horrified. And yet they adopted the seeds. Why?

Well they didn’t at first. In fact, the whole field of research on adoption of technologies — “innovation diffusion” research — got its start in 1942 when Iowa breeders hired some sociologists to figure out why farmers were not adopting the new hybrids.

One reason was simple: even with publicly-supported breeders doing all that legwork to find winners for the seed companies, the hybrids were only marginally better than the conventional seeds. And they had to be bought every year. And they were pricey.

But hybrid corn enjoyed an unprecedented level of promotion by corn breeders. As employees of public institutions, the breeders were supposed to have the farmers’ interests at heart; but then again so had the selectionist breeders they had vanquished as they staked their careers on hybrids. And they had a powerful new means of getting into farmers’ ears: farm radio was spreading just as hybrids were being introduced [10].

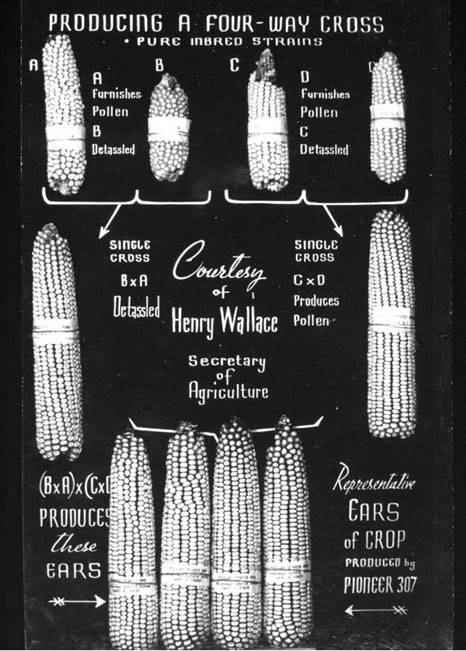

And hybrid corn was being pushed by the full persuasive power of the federal government because the seed industry had infiltrated the USDA at the top: FDR’s Agriculture Secretary was none other than Henry A. Wallace, whose Pioneer Hybrid Seed Company was the nation’s largest seed hybrid seed seller.

Wallace wasted no time in putting the full weight of the Federal government behind a sustained propaganda campaign to promote hybrid corn — despite his glaring conflict of interest [13].

Another factor was drought and desperation. The 1930s not only brought farmers the hardships of the Depression and the grain surplus, but a severe droughts in 1934 and 1936. Reeling from these compound threats to their livelihood, farmers in the Midwest began to hear that the new hybrids had weathered the drought better than conventional corn. In particular Pioneer’s new 307 hybrid was said to have had lower yield reductions. This kicked off a jump in hybrid adoption, which eventually led to what has been called a snowball effect. Farmers, it turns out, are surprisingly prone to bandwagons — and this is well documented [4, 14, 15].

Were hybrids really more resistant to the 1930’s droughts? Maybe , but then again the main source this claim was the Pioneer Hybrid Corporation, amplified by Secretary Wallace. Moreover hybrids’ “superior performance” would have been a textbook case of selection bias: it is known that the “early adopters” who were the first to try out hybrids tended to be the most successful farmers, the very ones who could afford to devote the most attention to the crops and probably even plant the fancy new seeds on their best land.

And by the mid-1930s, the conventional “selectionist” breeding that had served farmers so well for decades had shriveled to almost nothing as public institutions poured their resources into developing hybrids. In 1924, 99% of the entries in the Iowa Corn Yield test were OPV’s; by 1938 less than 6% were OPV’s [16].

Looking Ahead

If the input-intensive, over-producing corn hybrids were a disaster in the 20th century, they are likely to be even worse in the 21st. Notice that while corn yields certainly trend upward, they became highly unstable after the 1960s, with dramatic dips over and over again. The early hybrids may have been relatively drought resistant, but the water-intensive seeds that spread in the 1960s were anything but. In fact, a 2-week drought just when the crop is pollinating can easily cut production by a quarter; a continuous drought may result in 100 percent reduction. [17].

You would think that no farmer in their right mind would plant much of such a risky crop, but remember that American farmers are floating on a sea of supports and subsidies. Every time the hybrid yields crash, a plethora of government programs — like the Federal Crop Insurance Program, the Noninsured Crop Disaster Assistance Program, the Emergency Loan Program, the Emergency Commodity Assistance Program — open their wallets.

At the end of the day, we have not only spent a taxpayer fortune subsidizing farmers to use toxic chemicals to grow vast quantities of uneconomic and unneeded corn, but to do so with hybrids that are highly unstable in weather extremes.

In a world increasingly confronted with weather extremes.

And still we celebrate a chart of progress of hybrid corn.

References

1. Kloppenburg, J.R., Jr, First the seed: the political economy of plant biotechnology, 1492-2000, 2nd edition. 2004, Madison: Univ Wisconsin Press.

2. Just a few examples: Bórawski, P 2015 Multifunctional development of rural areas: international experience; Brummel, D 2022 A Brief History of Corn – From Domestication to 1995 (Pioneer website); Kloppenburg 2004 [above]; Kucharik, C and N Ramankutty 2005 Trends and Variability in U.S. Corn Yields Over the Twentieth Century. Earth Interactions – EARTH INTERACT 9; Larsen, J 2012 Heat and Drought Ravage U.S. Crop Prospects—Global Stocks Suffer. in Grist Magazine; Mitchell, P 2018 Corn Productivity: The Role of Management and Biotechnology; Nielsen, R.L. 2023 Historical Corn Grain Yields in the U.S., in Corny News Network. Purdue Univ.; Perry, M 2011 Corn Yields Have Increased Six Times Since 1940, in American Enterprise Inst.; Pesticide Guy 2014 Herbicide Adoption Contributed Greatly to Increased Corn Production, on Pesticideguy.org.

3. Stone, G.D., Skill Talk: The Struggle Over Agricultural Decision-Making. Outlook on Agriculture, 2025.

4. Stone, G.D., The agricultural dilemma: How not to feed the world. 2022, London, New York: Routledge.

5. Wallace, H.A., The year in agriculture: secretary’s report to the president, in Yearbook of Agriculture. 1934, USGPO: Washington, DC. p. 1-99.

6. Culver, J. and J. Hyde. 2000. American Dreamer: The Life and Times of Henry A. Wallace. New York and London: W.W. Norton, pp. 123–124.

7. Cullather, N., The hungry world: America’s cold war battle against poverty in Asia. 2010, Cambridge MA: Harvard Univ. Press.

8. Montgomery, D.R., 2020 visions: Soil. Nature, 2010. 463(7277): p. 26-32.

9. Fitzgerald, D., Every farm a factory: the industrial ideal in American agriculture. 2003, New Haven & London: Yale Univ Press.

10. Novaes de Amorim, A., Agricultural Change in the United States: Evidence from the Golden Age of Radio. 2023: Unpublished paper.

11. Fitzgerald, D., Farmers Deskilled: Hybrid Corn and Farmers Work. Technology and Culture, 1993. 34: p. 324-43.

12. For instance, see Gunderson, P., et al. The Epidemiology of Suicide Among Farm Residents or Workers in Five North-Central States, 1980–1988. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 1993, 9(3), 26–32. This multi-state analysis (1980–1988) of five Midwestern states reported exceptionally high suicide rates among male farmers — annual rates ranging from roughly 42 to 58 per 100,000, far above other farming groups. Farmers and ranchers were about 1.5 to 2 times more likely to die by suicide than other U.S. men.

13. Sutch, R., The Impact of the 1936 Corn Belt Drought on American Farmers’ Adoption of Hybrid Corn, in The Economics of Climate Change: Adaptations Past and Present, G.D. Libecap and R.H. Steckel, Editors. 2011, University of Chicago Press: Chicago. p. 195-223; Sutch, R.C., Henry Agard Wallace, the Iowa Corn Yield Tests, and the Adoption of Hybrid Corn. 2008.

14. Stone, G.D., A. Flachs, and C. Diepenbrock, Rhythms of the herd: Long term dynamics in seed choice by Indian farmers. Technology in Society, 2014. 36: p. 26-38.

15. Stone, G.D., Agricultural Deskilling and the Spread of Genetically Modified Cotton in Warangal. Current Anthropology, 2007. 48: p. 67-103.

16. Robinson, J.L. and O.A. Knott, The story of the Iowa Crop Improvement Association and its predecessors. 1963, Ames IA: Iowa Crop Improvement Association. 269 p.

17. Berglund, D., G. Endres, and D.A. McWilliams Corn growth and management. North Dakota State University extension, 2020.